In Mexico, día de los muertos (Day of the dead) brings a spirit of celebration and an explosion of color to the pueblos in the first couple days of November. The cemeteries glow with candles and fresh marigolds, music and the sound of laughter echo throughout, blanketed by old stories of great ancestors. The plazas are spilling over with special ofrendas reaching six feet wide and sometimes 20 feet long, stretching out on the ground with flower petals formed into intricate designs, to the soundtrack of mariachis parading through the streets gathering mysterious dancing catrins and catrinas.

In our homes, we create our own ofrendas, complete with guiding spirit animals and the foods and drinks loved by our family members who have crossed over to lure them to come home for one night to celebrate with us. It has been my favorite holiday since moving our family to Mexico and I spend weeks creating our ofrenda (altar of offerings) to bring my family home.

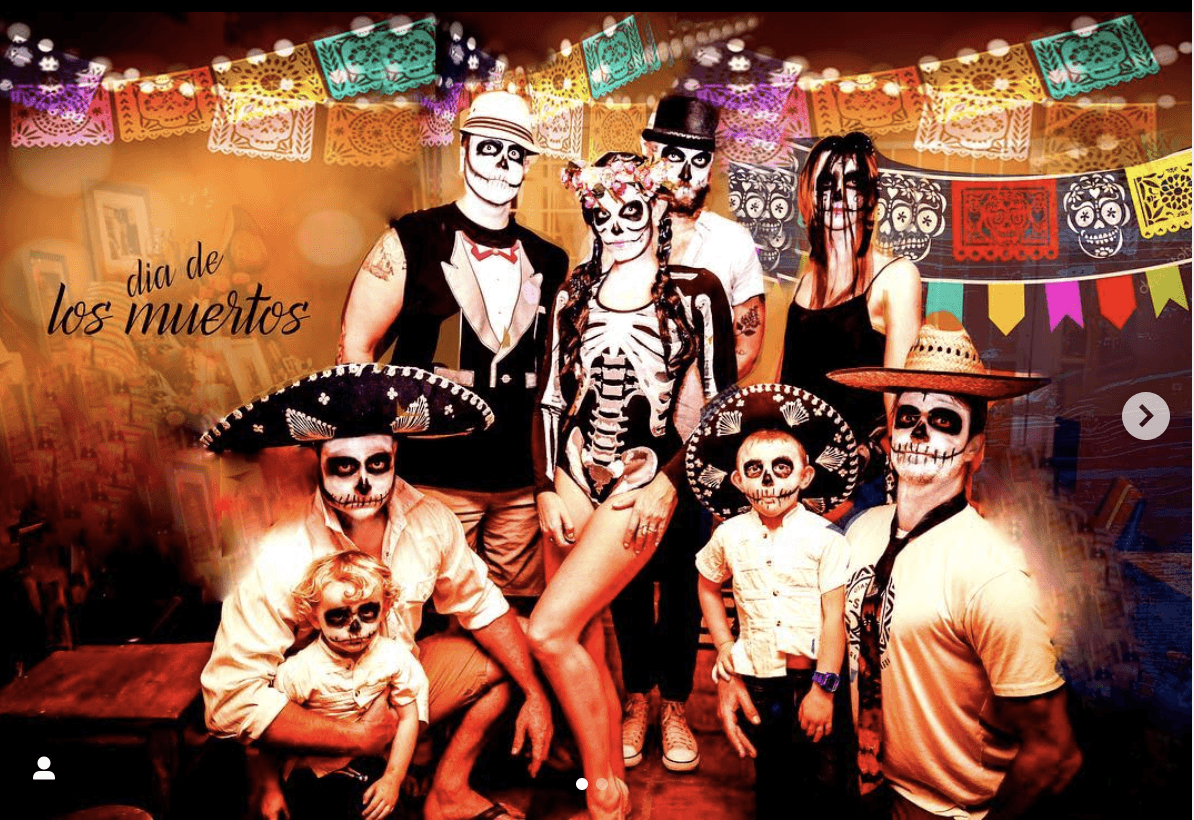

Legend says that the dead would be offended by mourning or sadness, so Dia de los muertos celebrates their lives with fine cuisine, cocktails and parties… all the things they enjoyed on this side. Today, November 2nd is the official day for adults who have passed and today, like always, we will have a grand fiesta with our families combined! Viva La Catrina!

The history of Dia De los Muertos dates back to the Aztecs who worshipped a goddess of death, her name was Mictecacihuatl, the Lady of Mictlan, the underworld. Also known as Lady of the Dead, Mictecacihuatl was keeper of the bones in the underworld, and she presided over the ancient monthlong Aztec festivals honoring the dead. With Christian beliefs superimposed on the ancient rituals, those celebrations have evolved into today’s Day of the Dead.

The history of Dia De los Muertos dates back to the Aztecs who worshipped a goddess of death, her name was Mictecacihuatl, the Lady of Mictlan, the underworld. Also known as Lady of the Dead, Mictecacihuatl was keeper of the bones in the underworld, and she presided over the ancient monthlong Aztec festivals honoring the dead. With Christian beliefs superimposed on the ancient rituals, those celebrations have evolved into today’s Day of the Dead.

It is believed that the goddess of death allegedly protected their departed loved ones, helping them into the next stages. The Mexican tradition of honoring and celebrating the dead is entrenched deeply in the culture of its people. For these pre-Hispanic cultures, death was a natural phase in life’s long continuum. The dead were still members of the community, kept alive in memory and spirit—and during Día de los Muertos, they temporarily returned to Earth.

In 1947 artist Diego Rivera featured the original Catrina design by Jose’ Guadalupe Posada of his stylized skeleton in his masterpiece mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.” Posada’s skeletal bust was dressed in a large feminine hat, and Rivera made his female and named her Catrina, slang for “the rich.” Today, the calavera Catrina, or elegant skull, is the Day of the Dead’s most ubiquitous symbol.

“Catrina has come to symbolize not only El Día de los Muertos and the Mexican willingness to laugh at death itself, but originally catrina was an elegant or well-dressed woman, so it refers to rich people,” said David J. De la Torre (curator of San Francisco’s Mexican Museum). “Death brings this neutralizing force; everyone is equal in the end. Sometimes people have to be reminded.”

The Day of the Dead brings into focus one of the greatest differences between Mexican and U.S. cultures: the 180-degree divide between attitudes toward death. Mexicans keep death (and by extension their dead loved ones) close, treating it with familiarity — even hospitality — instead of dread. La Catrina embodies that philosophy, and yet she is much more than that.

“Even though the Catrina it is now very popular, many people do not know its significance and they associate it with something dark, which is a mistake,” Said Marina Lozano, an arts and craft teacher from Guanajuato, Mexico “The Catrina is something spiritual.”

“It is a form of unifying humanity because at the end we will all be just skeletons,” Lozano added. “In Mexico, we have always had adoration and admiration for skeletons… so we are not afraid, we love the bones that represent our ancestors.”

National Geographic magazine has broken down the traditions of Dia de los Muertos and the history of such iconic pieces of the celebration.

The centerpiece of the celebration is an altar, or ofrenda, built in private homes and cemeteries. These aren’t altars for worshipping; rather, they’re meant to welcome spirits back to the realm of the living. As such, they’re loaded with offerings—water to quench thirst after the long journey, food, family photos, and a candle for each dead relative. If one of the spirits is a child, you might find small toys on the altar. Marigolds are the main flowers used to decorate the altar. Scattered from altar to gravesite, marigold petals guide wandering souls back to their place of rest. The smoke from copal incense, made from tree resin, transmits praise and prayers and purifies the area around the altar.

In the early 20th century, Mexican political cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada created an etching to accompany a literary calavera. Posada dressed his personification of death in fancy French garb and called it Calavera Garbancera, intending it as social commentary on Mexican society’s emulation of European sophistication. “Todos somos calaveras,” a quote commonly attributed to Posada, means “we are all skeletons.” Underneath all our manmade trappings, we are all the same.

Day of the Dead is an extremely social holiday that spills into streets and public squares at all hours of the day and night. Dressing up as skeletons is part of the fun. People of all ages have their faces artfully painted to resemble skulls, and, mimicking the calavera Catrina, they don suits and fancy dresses. Many revelers wear shells or other noisemakers to amp up the excitement—and also possibly to rouse the dead and keep them close during the fun.

You’ve probably seen this beautiful Mexican paper craft plenty of times in stateside Mexican restaurants. The literal translation, pierced paper, perfectly describes how it’s made. Artisans stack colored tissue paper in dozens of layers, then perforate the layers with hammer and chisel points. Papel picado isn’t used exclusively during Day of the Dead, but it plays an important role in the holiday. Draped around altars and in the streets, the art represents the wind and the fragility of life.

If you ever get a chance to visit Mexico during Dia De los Muertos, you will not be disappointed. Rich with culture and tradition, Mexico inspires us to adopt these beautiful events of celebration into our own lives and add tradition for our families to come. Feliz dia de los Muertos!